AI and Young People

Written by: Valentin Neshovski

Artificial Intelligence is no longer a “future technology” for young people. It is already part of how they study, write, code, design, communicate — and increasingly, how they imagine their future careers. The real question is no longer whether AI will shape youth lives, but how well-prepared young people will be to influence how AI develops.

How widely have young people accepted AI?

What is important when asking whether young people are adopting AI is that, unsurprisingly, the adoption curve is extremely steep — like the slopes of the Matterhorn in the Alps — and still rising.

Here are the key data points:

26% of U.S. teenagers say they already use ChatGPT for schoolwork, double the figure from just two years earlier (Pew Research Center, 2025)

Among students, ChatGPT dominates the chatbot space, with nearly 60% of teens using it, far ahead of alternatives (Pew, 2025):

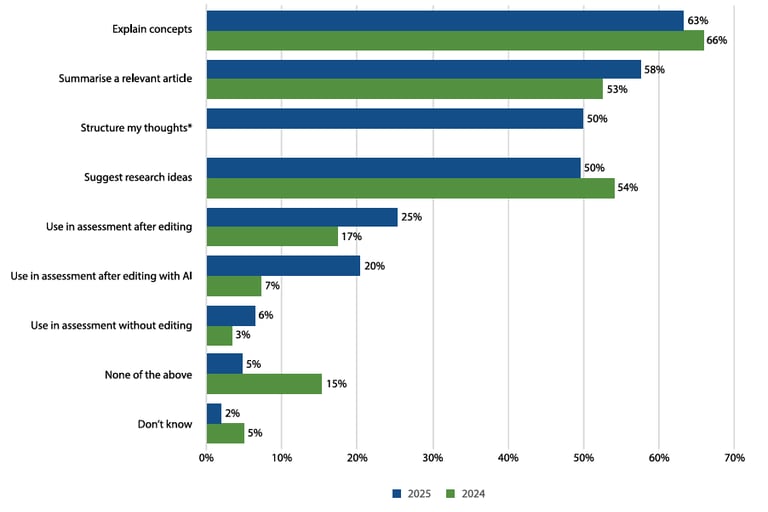

In UK higher education, 92% of students report using AI, and 64% admit using it to generate text (HEPI & Kortext Student Survey, 2025):

Figure: Which of these are acceptable uses of generative AI for assessments

It seems that AI is not a fringe habit. It’s already closer to “calculator-level normal” than to “experimental tech.” Trying to ban AI in schools outright is like banning Google in 2005 — technically possible, practically pointless.

What do young people actually use AI for?

The myth among the older population is that the young people use AI for fun conversations or to cheat while studying. The reality: they mostly use it to cope or to learn more easily.

Common uses according to surveys include:

explaining complex topics (“Explain quantum mechanics like I’m 12”)

summarizing long readings (because nobody has time anymore)

drafting and editing text

brainstorming ideas

debugging code

language learning

What is important is that most young people don’t use AI to avoid thinking — they use it because the education system still assumes infinite time and zero cognitive overload. It seems that the AI fills the gap left by outdated curricula and under-resourced teaching.

Are there any real risks?

The risks are real — but often misunderstood.

UNESCO warns that uncritical AI use can weaken core skills if education systems fail to adapt:

In other words – the claim is that If students only ask AI for answers instead of for explanations, they may pass exams today and struggle tomorrow. Some researchers think that this curve will be downslope since the AI will be part of everyday life and the habits for quick and unsubstantiated answers will reach minimal plateau when the real work is at stake.

Other risk when it comes to the psychological sphere is the AI hallucinations and providing false confidence for users. AI is excellent at sounding right — even when it’s wrong. AI is like that confident classmate who answers every question loudly. Sometimes brilliant. Sometimes completely wrong. Teachers still matter.

When it comes to the privacy and data risks UNICEF highlights that young user often don’t understand where their data goes or how it’s reused:

Having the former in mind AI literacy is at utmost importance and must include digital rights, not just technical skills.

Will AI destroy youth employment?

Short answer: No. But it will destroy “easy beginnings.”

The World Economic Forum expects major job churn by 2030, not mass unemployment — but entry-level roles will change fast:

Many education experts are detecting that routine junior tasks (basic writing, simple coding, reporting) are being automated. It is said that employers now expect judgment, not just execution.

In other word s - “I know Excel” is the new “I can type.”

It can be concluded that AI won’t replace young people — but it will replace young people who bring nothing except tasks that AI can already do better, faster, and without coffee breaks.

What should young people actually learn?

There are several layers to comprehensively answer this question in which core the notion is that policy often fails.

Layer 1: AI literacy should be mandatory for everyone. Many countries, China for example, are introducing AI in the school entry level i.e. kids at 7-10 years old.

AI literacy should include:

how AI works (at a conceptual level)

where it fails

how to verify outputs

how to ask better questions (prompting as thinking, not magic)

UNESCO and OECD both emphasize this as a core future skill, not an elective.

Layer 2: “Human advantage” skills

These are the skills AI amplifies — not replaces:

critical thinking

structured writing

ethics and responsibility

creativity with taste

collaboration

Shortly - the future belongs to people who can argue with AI, not blindly accept it.

What to expect in 2026

The I-HI Think Tank conducted in-depth research, and the general conclusions for 2026 are the following:

Schools in developed world will formalize AI policies instead of pretending it doesn’t exist.

Employers will assume basic AI fluency.

The EU AI Act will start shaping how AI is deployed in education and work:

McKinsey already reports 65% of organizations regularly using generative AI:

AI skills will stop being “extra” and become baseline.

What about the next five years?

By 2030, the biggest change won’t be technological — it will be cultural.

Degrees matter less; portfolios matter more.

Learning becomes continuous, not front-loaded.

“AI + discipline” beats “AI + shortcuts.”

Young people who can combine domain knowledge with AI tools will compete globally — from anywhere.

For young people, the question is already simple and uncomfortable: Will AI multiply your thinking — or replace it?

The answer depends far more on policy decisions of each and every state, education choices, and personal discipline than on the technology itself.